Can America regain global leadership? The question reflects the shock and dismay with which foreign policy establishments in North America and Europe greeted and viewed Donald Trump’s election as the 45th president of the United States. They came to regard what Trump said and did in office between 2017 and 2021 as a repudiation of common Western values and the retreat of the US from leadership. In this narrative, the Biden administration is now heroically struggling to restore American global leadership.

It is a nice story. But this emotional and ideological narrative is premised on a particular—largely mythical—notion of American leadership. In reality, mistrust of multilateralism, ambivalence toward free trade, insistence on fairness, a preference for bilateralism, transactionalism in relationships, and a penchant for unilateral action—all characteristics of Trump’s foreign policy—were not his personal inventions. The Shining City on a Hill has always cast dark shadows, and these traits have always been present in American foreign policy, at least to some degree. The overall contrast between Trump and his predecessor obscured this reality to those already shell-shocked by his election.

Asia’s response to Trump was less emotional and more pragmatic. America’s allies and partners in Asia understood better than Europeans or North Americans that “leadership” is what the leader does, irrespective of whether or not you approve of their actions. The really crucial question is not whether America can “regain” leadership, but whether or not you have a choice—a choice of whom to accept as leader and for what purposes.

Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, New Zealand, and the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations were not happy with every Trump policy. His repudiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership was a serious blow. But faced with an assertive China and a nuclear North Korea, they understood that regional balance of power and deterrence was impossible without the US, and that in this respect, the Obama administration was not some prelapsarian paradise.

America’s relations in Asia have been based on shared interests far more than on common values. Although values are not inconsequential to the American relationships in Asia, common values arise from shared interests and reinforce them; however, they are not a substitute for shared interests. Rather, shared interests must fundamentally rest on calculations about the utility of American power.

This is important because—except for a short and historically exceptional period between 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down, and circa 2008, when the global financial crisis broke out—American leadership has always been contested, both globally and internally in specific countries. Even during the Cold War, American allies did not accept all aspects of American leadership and often questioned it, although not on core issues.

The global financial crisis led to disillusionment with US-led globalization in many countries, including America itself. It was a major factor leading to China’s premature abandonment of Deng Xiaoping’s sage approach of “hiding light and biding time” in the belief that America was in irrevocable decline, reinforced by Obama’s perceived lack of stomach for the harsh realities of competition and his reluctance to use power.

China made a strategic mistake. Assertive Chinese behavior catalyzed concerns that had been brewing for some time in many countries, igniting a new competitive dynamic between the US and China. But China, and in particular Xi Jinping, cannot retreat without looking weak. This would be domestically disastrous for the Chinese Communist Party, and it will press on. Equally, no US president wants to be regarded as weak. In both the US and China, domestic politics drive strategic competition.

Trump and senior US officials meet Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires, 2018. Photo credit: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

We have now returned to a more historically normal period of contested American leadership. It is all the more important, therefore, that we are clear-eyed about our interests. Perhaps instinctively and however clumsily, Trump understood the use of hard power far better than Obama. When Obama drew a red line in Syria but failed to enforce it, the credibility of American power everywhere was degraded. When Trump bombed Syria while at dinner with President Xi, America’s friends and adversaries alike sat up and took note. Biden is clearly determined not to be Obama 2.0, at least not in Asia. Among his administration’s first actions was to pointedly exercise hard power in the South and East China Seas and the Taiwan Straits.

Still, after 40 years of Cold War and seemingly interminable post-9/11 wars in the Middle East, it has been clear for a decade or so that ordinary Americans are no longer willing to bear any burden or pay any price to uphold global order. Despite their obvious differences, Trump and Obama were manifestations of this new political mood. Neither came from the traditional American political establishment; they were the first truly post–Cold War presidents. When Obama was elected on the slogan of “Change We Can Believe In,” American voters did not understand this as change abroad but rather as change at home. In other words, it was time to put America first.

This was less the retreat from leadership as some portrayed it than a demand that American allies and friends should bear more of the burdens of upholding order. Former Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo was perhaps the first world leader to recognize this. During his second term that spanned both Obama and Trump’s presidencies, working quietly through administrative changes and without formally revising Japan’s pacifist constitution, Abe transformed the US–Japan Alliance into a more equal partnership and expanded the range and scope of missions that the Japan Self-Defense Forces could undertake in the common defense.

By contrast, Angela Merkel returned from her first meeting with Trump to tell EU leaders, with an air of great surprise—as if she had been struck by an epiphany in the White House—that Europe would henceforth have to rely more on itself. But that was only a much belated realization of what every American president since Bill Clinton had been telling the Europeans—perhaps too gently to make an impact—to take more responsibility for your own security and the burdens of the common defense.

Post-Soviet Russia is not an existential threat to America, but Europe without America is incapable of dealing with Russia, and NATO without the US is hollow. Europe has been a free-rider on the US for far too long, and it has yet to find the political will to substantially increase defense budgets, as it requires the politically dangerous shrinking of an overly generous social model that is unsustainable as a matter of actuarial certainty. Instead of contributing to the common defense, Europe prefers to talk of common values.

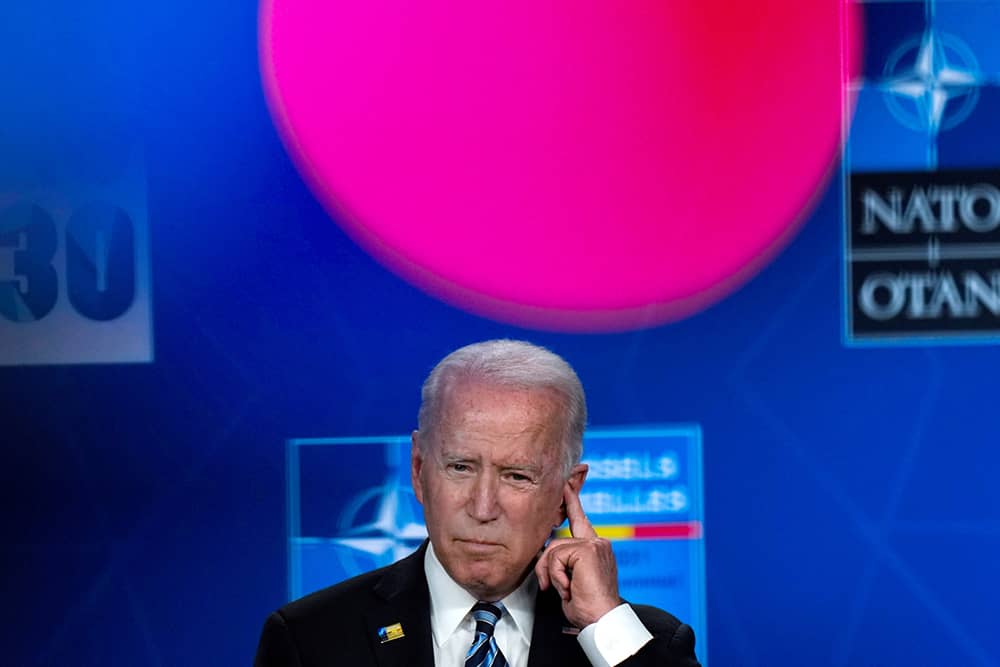

Biden clearly takes the idea of common values more seriously than Trump. He described his June trip to Europe as America’s rallying of the world’s democracies. He has demonstrated by word and deed that he intends to take a more consultative approach toward allies and partners. This is all for the good. But America’s allies and partners everywhere should understand that the corollary to a more consultative approach is a higher expectation of cooperation—a politer form of transactionalism. If you expect to be consulted, be prepared to do more on issues that America considers important, because consultation and emphasis of common values are not ends in themselves.

Not very much separates Biden’s “Build Back Better” from Trump’s “America First.” Even less space divides Trump’s approach toward China and Biden’s China policy, which is, in essence, Trump’s approach, implemented and communicated in a more orderly manner without unnecessary histrionics. China is now America’s core issue, the only issue on which there is a strong bipartisan consensus.

The Biden administration’s first contacts were with its Asian allies and partners because Asia is the epicenter of US–China competition. Although the Middle East can never be ignored nor will Israel ever be abandoned, the Middle East is not among the first order of American interests any longer. The broader meaning of the Abraham Accords is “rely more on yourselves.” Iran will increasingly be considered only as a function of Tehran’s relationship with Beijing. The extent to which the Middle East can rely on American leadership will depend on the roles the countries in the region can or are prepared to play in the US–China strategic contest.

To position ourselves in this new situation requires us to accurately understand the nature of US–China competition. It is not a “new Cold War”; that is an intellectually lazy and overused trope that fundamentally misrepresents the nature of US–China competition.

The US and the Soviet Union led two separate systems connected only at their margins. Their Cold War competition was to determine which system would prevail. By contrast, the US and China are both vital and irreplaceable components of a single global economic system. Their competition is to determine who will dominate this single system. Competition within a system is fundamentally different from competition between different systems.

There are important political differences between the authoritarian communist Chinese system and the liberal–democratic American system. But we should not lose sight of the fact that the US and China are both mixed economies, their differences being in the balance between the planned or regulated elements and the free-market elements. These are differences of degree, not of kind, which in the 21st century may prove as decisive, if not more so, than political differences.

This possibility is perhaps more obvious to a small country like mine that is neither authoritarian in the Chinese mode nor liberal–democratic in the American mode, and which has had occasion to call a plague on both houses.

The single global system is defined by a web of supply chains of a scope, density, and complexity that is historically unprecedented; nothing quite like it has ever existed before in the global economy. It enmeshes the US and China with each other and with other economies in interdependence of a qualitatively new type that simultaneously drives, shapes, and complicates a new kind of geopolitical competition in which economics play a more crucial and direct role than during the US–Soviet Cold War when economic considerations were secondary or only instrumental. The Soviet Union was never a significant economic player, except in the oil and natural gas markets.

The complex and dense web of supply chains makes it extremely improbable that, whatever their intentions, the US and China will ever decouple or bifurcate into two entirely separate systems. Bifurcation of a great degree has already occurred in some specific domains—for example, the internet has largely separated—and bifurcation of some degree will probably occur in other domains, but across-the-board bifurcation encompassing all domains is well-nigh impossible at any acceptable cost.

The consequence is ambivalence. This is the characteristic attitude of this new phase of international relations. The US and China eye each other with wary ambivalence; they are profoundly interdependent but deeply distrustful of each other, precisely because they are so interdependent. Confronted with the twin realities of a more assertive China and a more transactional America, ambivalence also infuses the way third countries regard the two. No one wants to make an enemy of either China or the US; no one can do without having a relationship with both; and everyone has some concerns about the two.

The result is a greater fluidity in international relationships, which imparts a new meaning to the idea of global leadership. For third countries, the imperative is to maximize strategic autonomy. No country is likely to neatly align interests across all domains with either the US or China to the exclusion of the other. Sometimes we will need to lean one way, sometimes the other way, and sometimes we will have to go our own way, while trying not to go so far as to irretrievably damage relations with either Washington or Beijing.

This requires an entirely new set of strategic instincts. Asia has lived with the complexities of the competition between the US and China for much longer than the Middle East. But navigating the new complexities is not easy for anyone and requires great agility of mind and policy. Still, bear in mind that the new complexities offer, at least in principle, greater agency than the narrow and essentially binary Cold War system—if only we have the wit to recognize it and the courage to use it.