The Jerusalem Strategic Tribune mourns the passing of Professor Aharon Klieman, one of our first contributors and a leading light in the community of Israeli scholars concerned with world affairs. Read his eulogy by Dr. Yoel Guzansky.

American foreign policy has traditionally honored the concept of the balance of power in practice, while negating it in theory. This paradoxical disconnect between word and deed has continued almost uninterrupted throughout the post-1945 world order to the present, coloring the American approach to regional and global affairs, including policies toward the Middle East.

The Isolationist Impulse

Historically, this a priori disqualification of the balancing principle as an ordering concept for basing a realistic strategy traces back to the founding of the New World republic and its early faith in its exceptionalism. Otherwise preoccupied with solidifying their own country’s newly gained independence, Americans did take cognizance of Poland’s dismemberment (1772, 1793, 1795) in the name of preserving an Old World balance among contending European powers. This undoubtedly left a deep imprint on the American psyche. If nothing else, such an act of brute, naked force led the generation of founding fathers to recoil from territorial partition, imperialism, and similar coercive practices associated with power politics.

In 1764 Benjamin Franklin wrote in his distinctive style: “Abroad, the Poles are cutting one another’s throat a little … if they are fond of this Privelege [sic], I don’t know that their neighbors had any right to disturb them of the enjoyment of it.” While most commentators faulted Poland for its internal divisiveness, the fact remained, as Alexander Hamilton noted, that Poland was long at the “mercy of its powerful neighbors.”

Thus, already at an early, formative stage, the isolationist impulse expressed itself in an aversion to foreign entanglements. The same sentiment applied to the balance of power’s imperative for eternal vigilance, constant involvement, and ceaseless maneuvering on behalf of narrow self-interests. These measures—so central to the workings of balancing and counterbalancing (i.e., “the Game of Nations”)—ran directly counter to America’s self-perception as a nation apart and above.

With the emergence of the United States as a major actor in the immediate post-1918 world order, this moralistic opposition to the balance of power—as alien to American values and as the root cause of the European catastrophe—not only came to dominate American thinking but also became declaratory policy. Addressing the US Senate on January 22, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asserted, “There must be, not a balance of power, but a community of power; not organized rivalries, but an organized common peace.” Ideas embodied in neo-liberal Wilsonianism continue to resonate in present-day foreign policy discourse.

Photo credit: REUTERS/Handout via US Library of Congress

Confirmation of this deeply ingrained conceptual and intellectual bias against the Realist school of thought—and its corollary, the concept of the balance of power—can readily be found today in both standard college course syllabi and scholarly journals devoted to international relations theory. The balance of power is either given short shrift, or else critiqued along the lines of Richard Cobden’s classic 1836 depiction as “a chimera”—“an undescribed, indescribable, incomprehensible nothing”—before being summarily dismissed as untenable on ethical grounds, inoperative in practice, and, for added measure, wholly irrelevant in today’s nuclearized world.

Save for this traditional aversion to the balance of power, American behavior abroad remains unanchored in any overriding conceptual or prescriptive framework for ordering an increasingly complex global system, and for defining the US role in promoting international peace and security. The absence of either consensus or consistency is mirrored at two levels: ideationally, by the still unsettled debate in professional literature over contesting alternative theories, and politically, by the pendular swing from one extreme posture to another in the modern history of American diplomacy—from estrangement to engagement and back.

Among the contending paradigms are idealism and its ultimate goal of world federalism; isolationism and neo-isolationism, popularized in slogans like “Fortress America” and “America First,” and pursued through policies of neutrality and appeasement; neoliberalism and its offshoot, liberal institutionalism; collective security; and the now discredited neoconservative zeal for aggressively transforming other nations’ politics. Added to the list in recent decades are two theoretical postulates for assuring the minimum of global stability, often mischaracterized as peace: the balance of terror, predicated upon rationality; and hegemony under enlightened US leadership.

Reluctant Balancer in Practice

Regardless of how much it is scorned in theory, and official disclaimers notwithstanding, in terms of actual practice, generations of US policymakers have relied upon alliances and a whole array of stratagems altogether consistent with the balance of power. They have done so compelled by sudden exigencies abroad or by direct threats from rival powers, yet without admitting as much, whether to themselves or to the American people.

The two world wars are outstanding cases in point. Breaking with tradition, in December 1917 and again in December 1941, the US in effect accepted and then filled the pivotal role of balancer—if not in averting, then at least in terminating major world conflicts. In each instance, America’s direct participation—however reluctantly embarked upon—proved decisive, tipping the scales against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) and the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) respectively.

Since achieving a decisive, transformative victory in 1945, the US is no longer a free agent or at liberty to chart its own independent course, unburdened by commitments abroad. Confronted almost immediately with a direct challenge (the so-called “Red Threat”) from the Soviet Union and international communism, Americans—against their inclination to turn inward—found themselves forced into a permanent state of alertness; once more they were thrust to the forefront of world affairs for the next half century. Adopting a Cold War doctrine of containment as a deterrent against communist-inspired destabilization and overt acts of aggression, on multiple fronts—Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—successive US administrations from Truman to Biden continue to behave in accordance with premises and practices at the very heart of balance-of-power thinking.

First and foremost, this is reflected by falling back upon the basic instrument of hard power. Responding to a series of crises at various flash points around the globe—ranging from the siege of Berlin (1945) to Lebanon (1958), the Cuban missile crisis (1962), Panama (1989), Kuwait (1991), and Iraq (2003–2011); and more dramatically, Korea (1950–1953), the Taiwan Straits (1954–1955 and 1958), and Vietnam (1954–1975) in the Far East—strategists have unfailingly prioritized the buildup of America’s military capability, with conventional power in the post-1945 era backed up by non-conventional nuclear weaponry.

Even following the final dissolution of the Soviet Union by 1991, this reliance on a show of armed force—once popularized as “gunboat diplomacy”—and its actual use when deemed necessary remains the linchpin of American political-military statecraft. It is the key to facing down the newest post-Cold War challengers to the status quo: China, Iran, and Putin’s Russia. No less familiar to students of the balance of power are the many standard nonmilitary levers available for calibrating power—and for preserving an existing favorable or equitable balance and for redressing an unfavorable one.

Whether it is through alliances such as NATO, used for burden-sharing and as force multipliers, or through competitive arms races, the US learned to use the other traditional levers for balancing power. This has included interventions aimed at regime change, the use of secret channels and espionage, divide-and-rule tactics, and encouraging defections—all aimed at weakening a rival alliance. Various forms of territorial adjustment like demilitarized and buffer zones, and not least, foreign aid with strings attached, as well as boycotts and sanctions under the heading of economic statecraft should also be included. As realists insist, these standard policy instruments are employed by all countries without exception, including the US.

Categorizing US foreign policy behavior, in terms of the balance of power, as unexceptional—rather than atypical—often puts liberal Americans in their ideological discomfort zone, as somehow betraying the foundational ideal of America as a beacon of light and hope for the world. This, in turn, may explain the pronounced tendency for high-ranking government officials to justify interventions abroad as undertaken for higher purposes: in defense of freedom, democracy, human rights, international peace, or, in other words, for any purpose save that of serving the balance of power while preserving or promoting the national interest.

Three Instances of Successful Balancing

A systemic effort at eliminating longstanding foreign policy dualism took place during the presidential administrations of Richard Nixon (1969–1974) and Gerald Ford (1974–1977), owing to the dominant influence of Dr. Henry Kissinger. In his White House years, first as national security advisor and then as secretary of state, Kissinger successfully bridged the gap between word and deed by unapologetically adopting the vocabulary of the balance of power while also applying it to the chessboard of world politics.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets Henry Kissinger in Beijing, in 2018. Photo credit: REUTERS/Thomas Peter

German-born, European in the older sense, and schooled in realpolitik, Kissinger also drew upon the teachings of Prof. Hans Morgenthau, the 20th century’s leading proponent of political realism. His contemporaries, many of them American-born charter members of the eastern establishment, operated from a conservative mindset whereby American foreign policy ought to be directed at preserving an existing state of affairs. Kissinger, by contrast, saw the wisdom as well as the necessity for the US colossus to seize initiatives and to create opportunities in the face of a status quo at once elusive and ephemeral.

Kissinger’s understanding of the dynamics of balancing—exhaustively analyzed in countless studies, some of them complimentary but more often than not deriding his Machiavellianism as deviant, “un-American” and “conduct unbecoming”—is best seen in the 1972 opening to China that fostered normalization with Asia’s rising power. In strategic terms, integrating China into the international system enabled the US in one masterful stroke to transform the basic geometry of the post-1945 world order. This move converted rigid bipolarity and stressful confrontation with Russia into tripolarity and shifted the tension to the Sino–Soviet axis while catapulting America into the privileged position of an uncommitted balancer solicited by both rival sides.

Second only to the China gambit was the US role in Middle East affairs, illustrating Kissinger’s application of the balance of power to real-world situations during his years in power. Taken by surprise at the sudden outbreak of hostilities in October 1973 between Egypt, Israel, and Syria, Kissinger adeptly exploited the acute crisis and resultant battlefield deadlock to insert himself and the US at the center of crisis management and to initiate what ultimately became a peace process: first, through carefully calibrated brinkmanship in facing down Brezhnev’s threat of military intervention, and then by all but excluding the Soviets from any role while patiently applying shuttle diplomacy and step-by-step negotiations. All this firmly established America’s credibility as a crucial third-party intermediary sought after by the Israelis as well as the Egyptians—and even the Syrians.

To grasp geopolitics as never-ending power-balancing among competitive state actors depends upon a realistic mindset and favorable predisposition rather than on the accident of personality. Resolute American policy throughout the 1990–1991 Kuwait crisis offers yet a third instance of successful balancing made intelligible only against the backdrop of growing American self-confidence at the dawn of the post-Cold War era.

With remarkably poor timing, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s invasion of neighboring Kuwait in 1990 coincided with the idea of yet another new world order then percolating through the corridors of power in Washington, with Iraq therefore providing its first test. Hence, there was heightened resolve of President George H. W. Bush and his secretary of state, James Baker, not to allow Iraq’s flagrant act of aggression to pass with impunity. To their credit, with a fixity of purpose, they patiently orchestrated a sophisticated diplomatic-legal-military campaign. They marshaled Security Council support under the United Nations Charter’s Article 51 for all “measures necessary to maintain international peace and security” together with formation of a multilateral coalition of 35 countries to compel Iraq’s withdrawal in 1991 from Kuwait. Moreover, they stopped short of ousting the Iraqi dictator from power, since this—in their mind—exceeded their own fixed purpose and threatened to turn a well-contained exercise of power into an open-ended entanglement.

Dispatching troops to unseat Saddam more than a decade later, in 2003, the US would then fall prey, however, to what Teddy White called the “Law of Unintended Consequences”—so characteristic of Middle East affairs—by undoing its own power-balancing policy of dual containment toward the two regional destabilizers: Baathist Iraq and Islamist Iran. An internally sectarian-divided and politically unstable Iraq thus opened the way for Tehran’s unchecked ascendancy around the Persian Gulf and in other parts of the Arab world. Political realism argues that returning to a status quo ante is a legal fiction even for superpowers; that foreign relations are never static or constant but dynamic; that diplomacy’s concern is not about the exact distribution of power (even or uneven? favorable or unfavorable?) but rather about balancing as an ongoing, never-ending process.

The US and the Middle East: Stay or Go?

Learned the hard way in Iraq and Afghanistan, this lesson about the futility of chasing after a stable equilibrium in the Middle East helps to explain the strong US desire to pivot away from the region. This may be in order to concentrate on domestic affairs, to redirect foreign policy elsewhere, or to respond to a major mood change that finds Americans no longer regarding themselves as the indispensable nation. The question, however, is not only what motivates America but the room for maneuver that Washington retains, or fails to retain, as it seeks to pursue its disengagement unimpeded.

The bitter experience of former Great Powers, Britain and France in particular—drawn into the maelstrom of 20th century Near and Middle East politics—provides a timely cautionary for the US. Likewise, Kissinger’s cautionary note that “in the end, peace can be achieved only by hegemony or by balance of power” deserves to be heeded. Applied to the Middle East, this poses three alternative strategies for the US. Hypothetically, at one extreme, it could return to acting like a hegemonic power by attempting to impose its will on supposedly weaker, subordinate local actors. At the opposite extreme is abnegation and, in effect, abandoning existing interests and allies and thereby creating in its wake a power vacuum to be filled by other players, especially potential rivals. In searching for a third, middle-of-the-road option, “selective balancing” becomes the sole plausible alternative—and, indeed, imperative.

Bin Salman and Sisi at the Presidential Palace in Cairo. Photo credit: Bandar Algaloud/Courtesy of Saudi Royal Court/Handout via REUTERS

If selective involvement and selective balancing are the realistic policy options, then in operative terms the first priority must be given to regaining clarity after years of confusion. Clarity of purpose serves as a prerequisite for a consensual redefinition of America’s core national interests in the region. This includes putting an end to the glaring policy inconsistency characterizing the Obama, Trump, and Biden presidencies on how to deal with Iran; on policy toward Syria and the Kurds; and regarding the derailed Arab–Israeli–Palestinian peace process and the two-state formula, among other regional issues.

Now that “doing it alone” is no longer US policy but “burden sharing” is, Mideast partnering becomes the next priority. This requires firming up ties with those regrettably few countries, regimes, and leaders sharing similar strategic goals, whose own domestic policies are judged compatible—but not identical—with American values. Much trickier are prospective allies like Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s Egypt and Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia, both proven strategic assets but whose record on democratic reform exposes them—and especially Washington’s policy toward them—to telling criticism.

Admittedly, selective balancing in the current Middle East will always be challenging from an American standpoint, primarily because of its proven volatility, whereby any single, usually unforeseen event can trigger a chain reaction unbalancing any given political equation. Take the 1967 and 1973 Israeli–Arab wars, for example, at an earlier stage; the 1979 Iranian revolution; or, most recently, the latest round of fighting in May over the Gaza Strip that may have been designed (but failed) to put the “Abraham Accords” in jeopardy.

But what makes the region singularly challenging at present is that, like the global system itself, the Middle East has become multipolar. Whatever their drawbacks, the Cold War system and then America’s unipolar moment, however brief or imagined, did provide a certain clarity because lesser and smaller powers knew their place within a hierarchical world order. This is no longer the case, least of all in the Middle East where the US finds itself one actor among any number of aspirants and competitors in a bewildering maze of intersecting multiple balances:

- Russia and China, investing heavily in select Arab and other regional target countries, pose a dual great power challenge to the US and would gladly welcome America’s self-imposed departure from a region they still regard as strategic.

- Iran, Israel, and Turkey—three independent-minded non-Arab regional powers—are in a triangular competition with each other. However, in continuing to distance himself from Jerusalem, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, at least for now, violates one of the cardinal principles of balancing by not banding together with Israel in order to offset the far greater threat posed by an expansionist, nuclearizing, militant Shiite Muslim Iran.

- The remaining smaller Middle East states and non-state actors like Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip are likewise in competition against each other; but they are also against admittedly more powerful regional and external powers, not excluding the US, whose “nefarious” role they seek to reduce.

Until a recent renewal of diplomatic ties, Qatar faced off against Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt. Removed from the public eye, the Palestinian Authority is in a longstanding contest with Jordan, a sovereign state, for proprietary rights over the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Yet a third example are efforts in recent months by Bahrain and other Persian Gulf emirates, not excluding even Saudi Arabia, at a form of balancing known as “hedging.” Prompted by insecurities resulting from ambiguous US policy toward Iran, they have adopted a more conciliatory attitude toward their geographically proximate and ascendant neighbor.

Obama walks past the Brandenburg Gate during his visit to Berlin, in 2016. Photo credit: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

Client states, which one might ordinarily assume to be dependent, are often, to the contrary, perfectly capable of testing and possibly even defying patrons. One can cite the unresolved tension since 2016 between a military superior Ankara and a politically fragile Syria, including periodic border clashes. Still better proof is Egypt’s 2019 decision to contract with Russia for advanced combat aircraft in open defiance of Washington’s threat to impose sanctions.

Treading carefully in such a complicated region leaves the US no room for illusions. Its regional supporters as well as adversaries need proof of America’s earnest intentions, its determination, and staying power. Moreover, the triple cross-cutting levels of accelerated balancing and counterbalancing—which allows for defiance, deception, and defection on the part of spoilers—demands of the US greater sophistication in monitoring the interplay of forces and in connecting the dots in order to avert crises and to seize opportunities.

Conclusion

The latest round of hostilities in the Gaza Strip, by way of summary, indicates why unflinching adherence to the rules of the balance of power becomes of cardinal importance for the US in contending with an unstable Middle East region in which several assertive actors seek center stage. In particular, the role of balancer—at once historical, privileged, and, above all, responsible—needs to be re-established.

Having been drawn anew into the conflict in effort to broker a cease-fire, the US, however warily, remains deeply and permanently involved as chief facilitator in moving beyond to some form of more permanent arrangement. President Biden, as holder of the balance by dint of America’s abiding power, prestige, and influence, will thus be compelled to maneuver within a triangle comprised of local parties, each in the dual capacity of unbowed and defiant dependents: Hamas, the de facto rulers of the Gaza Strip enclave; Israel, at times assertive and other times defensive; and the West Bank’s Palestinian Authority, the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people in name only.

Coming full circle to where this essay began, therefore, the precondition for selective balancing in the Middle East, as anywhere else in the international arena, mandates nothing short of a quiet revolution in America’s approach to world politics. Based upon performance rather than rhetorical flourishes, the US clearly does not play by a different set of rules. The time has come to restore realist balance-of-power thinking to the center of international relations theory and to give it pride of place in the open-ended great debate over the role of the US as the designated balancer in today’s decentralized multipolar world.

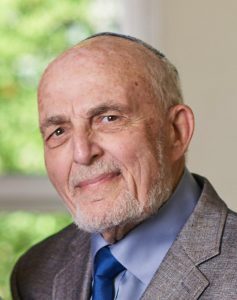

In Memoriam: Aharon S. Klieman (1939–2021)

Yoel Guzansky

In June we bade farewell to Professor (Emeritus) Aharon S. Klieman, one of Israel’s leading diplomatic historians. His contribution to The Jerusalem Strategic Tribune will unfortunately be the last. It is a powerful statement of his realist—and realistic—world view and a clarion call for clarity.

I had the privilege of being one of his students at Tel Aviv University. We met when he founded and headed the Abba Eban Graduate Program in Diplomatic Studies at Tel Aviv University.

Aharon joined Tel Aviv University in 1969 and was one of the founders of its political science department. He held the Nahum Goldmann Chair in Diplomacy and initiated projects such as the Round Table and International Forum at the university. Among his many activities, he was a senior research associate and a member of the Academic Advisory Board at the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (1978–2000). He educated generations of students, many of whom rose to hold key positions in Israel’s academic, security, political, and foreign affairs establishments.

As the author and editor of 22 books, 36 chapters, and 25 scholarly articles written in his 50-year career, he made an invaluable contribution to the field of international relations and the study of Israel’s foreign policy. Aharon received international recognition and was a guest lecturer at Georgetown University, the University of Chicago, University of Denver, University of Michigan, UCLA, Brown University, Trinity College Dublin, and other institutions.

After his retirement from Tel Aviv University, he founded and headed the School of Politics and Government at the Ashkelon Academic College. He chaired the Research Committee on Geopolitics of the International Political Science Association, and from 2010 served as the senior editor of the Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs.

Aharon was a true mensch and an academic ambassador of Israel abroad, who will be fondly remembered for his wisdom, warmth, and kindness in his encounters with professors and students alike. He was my friend and my mentor, and he will be greatly missed.

May his memory be a blessing, and may his work continue to inspire.