Recently I called up an Arab friend in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Kufr ‘Aqab. Having just returned from Israeli military reserve duty, I felt out of the loop and wanted to know what’s happening, especially why East Jerusalem’s Arab population seemed to react to this war differently than it had in previous rounds of Israeli-Palestinian violence.

My friend laughed, but answered in earnest. Listen, he said, we in Kufr ‘Aqab have much to lose. We already fear that any confrontation would have consequences. Making trouble may put our residence rights at risk. Furthermore, he added, not a few in the neighborhood, including his own family, have applied for Israeli citizenship and participating in disturbances would hardly help with that.

Most Maqdisiyyin, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem, are permanent residents but not citizens of Israel. They have equal rights under Israeli law to receive Israeli social insurance and Jerusalem municipal services and to vote in municipal elections. But the great majority have chosen not to apply for citizenship in the state, though they have the legal ability to do so.

In recent years, the numbers of East Jerusalemites applying for Israeli citizenship has risen, as the social stigma of becoming Israeli has begun to erode and despite an Israeli naturalization process that can take years and result in denial (because of the requirement to show Jerusalem residence or the need to pass a Hebrew language test). The number of East Jerusalemites granted citizenship has also risen, from 827 in 2009 to over 1,600 in 2020.

To make sense of the situation faced by my friend, one needs to understand the specifics of his neighborhood of Kufr ‘Aqab, which lies outside the separation barrier erected twenty years ago. There may be an emerging new reality in East Jerusalem which offers both improved conditions and a possibly better future for all in Jerusalem – Jews and Arabs alike.

Jerusalem as Symbol

This relative calm is all the more striking since Jerusalem, Al-Quds or the Holy One, is in many ways the symbolic focal point of the conflict. The names for Hamas operations invoke Jerusalem: in May 2021, Hamas and the Islamic Jihad in Gaza launched rockets into Israel under the banner of Ma’arakat Sayf al-Quds, The Sword of Jerusalem Operation, and now we are in the midst of Tufan al-Aqsa, the Al-Aqsa Flood.

There are several reasons for this centrality of Jerusalem. For centuries, Jerusalem was holy to the Muslims, albeit not the Muslim world’s political center. In the 8th century, under Islamic rule, the newly established coastal plain city of Ramleh, with its strategic location on the roads connecting Egypt and Syria, was the administrative capital of the province. In modern times, the Ottomans and then the British (the latter sometimes invoking a return of the Crusaders) restored Jerusalem’s political significance as the provincial capital.

The emerging Palestinian national movement, as it took shape in the 1920s, was in need of effective symbols. With Jerusalem as the holiest place for the Jewish faith and the third holiest for Sunni Islam, to which most Palestinians adhere, both sides would rally around this cause. Jerusalem was a central Jewish symbol – Zion is a name for Jerusalem. The Palestinian movement defined itself through the struggle to resist Jewish immigration and Jewish sovereignty. Then as now, the Zionist movement was not perceived by Palestinians as secular in nature, and for many Palestinians it is seen as a religious endeavor ultimately aimed at rebuilding the Temple on the ruins of the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

The importance and imagery of al-Aqsa and of the Dome of the Rock rose especially after they “fell in the hands of the Jews” in 1967 – serving the Palestinians’ quest to turn it into the cause of all Muslims (some 2 billion people) rather than just the Arabs (hundreds of millions) or the Palestinians alone (estimated at less than 15 million overall).

The symbolic centrality of Jerusalem to the conflict places a special burden on the Arabs of East Jerusalem who are torn, as my friend suggested, between their Palestinian, Muslim, and Israeli identities. This dilemma is further complicated as they see themselves as guardians of the Holy Places, a mission entrusted to them by Salah al-Din (Saladin) once he drove the Crusaders out of the city in the late 12th century.

East Jerusalem – Then and Now

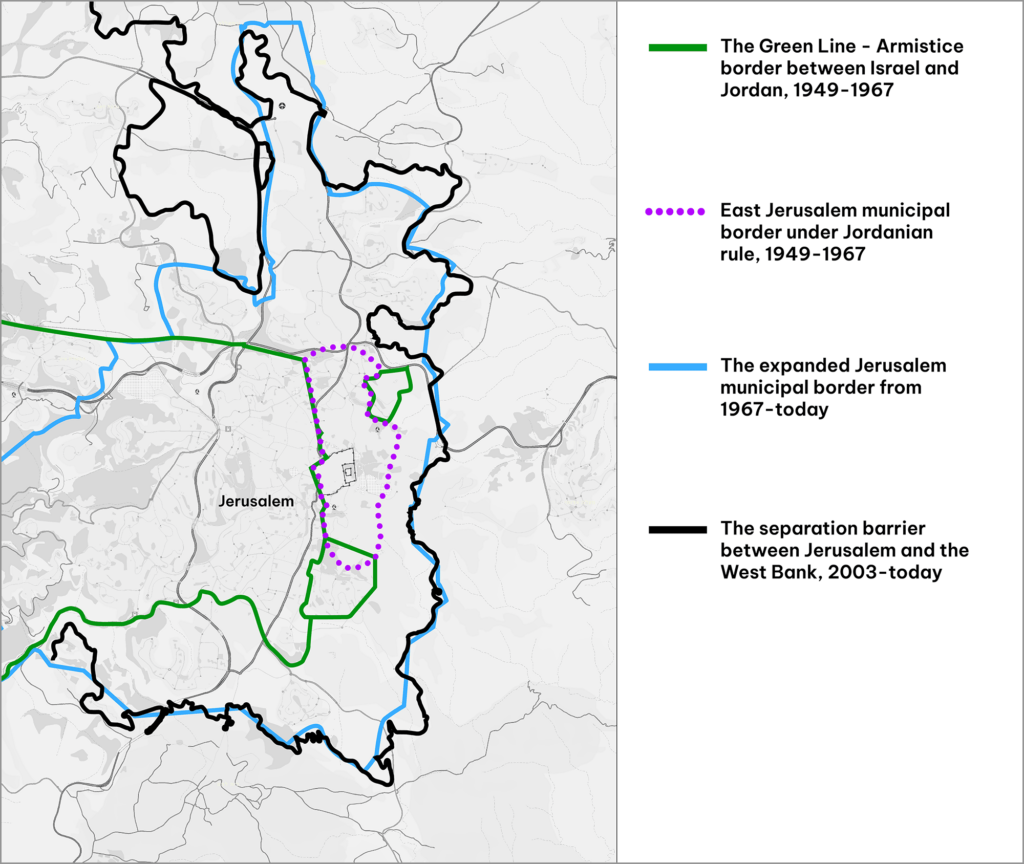

After the Six Day War of June 1967, Israel both expanded the borders of East Jerusalem and annexed the expanded municipality to Israel. About 65,000 Arab residents of Jerusalem and a few outlying villages in the expanded municipal area came under Israeli jurisdiction.

Today, owing to both natural growth and internal migration from the West Bank into the city, the Arab residents of the city number about 370,000, about 39 percent of the city’s population.

Though residents can vote in the municipal elections, few do so. In an interview in the 1990s, the long-serving Labor Party mayor of Jerusalem Teddy Kollek reflected on his legacy: “We bandied slogans about but did not deliver. We promised again and again that we would equalize the rights of Arabs in the city with those of the Jews – empty words… We never gave them a sense of equality before the law. They remained second or third class citizens. Yes, we did provide for sanitation and water supply, but that was because we feared the spread of cholera without it.”

Even today, Arab neighborhoods in East Jerusalem are neglected. Their electricity is still provided by a Palestinian company (which buys it from the Israeli Electric Corporation and then sells it with a 12 percent mark-up); public transport is run by local groups unaffiliated with the regular Israeli corporations; most neighborhoods still lack a master plan, and in the absence of building permits, illegal construction is rampant (which means the Israeli utilities cannot connect such housing to electricity and running water). The rate of poverty among East Jerusalem Arabs is among the highest in Israel – distinctly higher (at 60 percent) than among Israeli Arab citizens (39 percent).

The Causes of Neglect and the Turning Point

Explanations for this disparate treatment vary and tend to be politically colored. Deliberate ethnic discrimination played a role, perhaps in the minds of some Israeli extremists aimed at encouraging Arabs to leave. On the other hand, rejection of municipal services by Arab residents and even violent assaults on city workers – since their presence was perceived as illegitimate cooperation with the Zionist occupier – was another reason. The reluctance to vote for city hall added another factor: in a democracy, active constituents are courted and served and these residents generally don’t vote.

Another important reason for neglect and now for a shift in municipal policy was the level of uncertainty as to whether Israel would indeed retain East Jerusalem.

In May 1949, Israel annexed, under the terms of the armistice agreement with Jordan, a number of Arab towns and villages in the area of Wadi ‘Arah in northern Israel, including the present city of Umm al-Fahm. There, too, Arabs were offered the choice of becoming citizens of the new state of Israel – and within a few years all took the option. In Wadi ‘Arah, there was a certainty that their villages and towns would remain in Israel.

This certainty about East Jerusalem’s incorporation into Israel didn’t exist until recently. In numerous peace negotiations and planning efforts – the Oslo process, the Camp David talks in 2000 between Ehud Barak and Yasser ‘Arafat; the Geneva Initiative in 2003, and the Annapolis process launched in 2007 – the envisioned agreement would have involved a partition of Jerusalem under which the Jerusalem Arabs would become residents of the capital of Palestine, not of Israel.

Under such circumstances, can the mayors of Jerusalem be blamed for choosing not to build and develop in neighborhoods which may soon become part of a different state? And can East Jerusalem Arabs be blamed for not participating in the political and urban life in a country that may soon no longer be theirs – all the more so when the future Palestinian state may accuse them of treason if they did participate?

Uncertainty breeds, metaphorically, a fence-sitting mindset. As it turns out, what changed the mindset was a real, physical fence, which defined a border, served as a statement of intent, and changed the realities of daily life in the city.

In September 2000, the uprising known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada began. Once again Jerusalem was at center stage. In response to terror attacks, Ariel Sharon’s government erected a separation barrier between Israel and the West Bank; Jerusalem was one of the first sites where it was constructed.

The separation barrier for the first time physically separated East Jerusalem from the West Bank. The larger Arab metropolitan area extending from Ramallah, north of Jerusalem, to Bethlehem in the south was severed and fell apart. Families could no longer freely visit their relatives in Jerusalem. A distinct definition of East Jerusalem Arabs, who until then were somewhere between Israeli Arabs and West Bank Arabs, has begun to emerge. With it come their own preferences, beliefs, and political attitudes towards the Palestinian Authority and towards Israel.

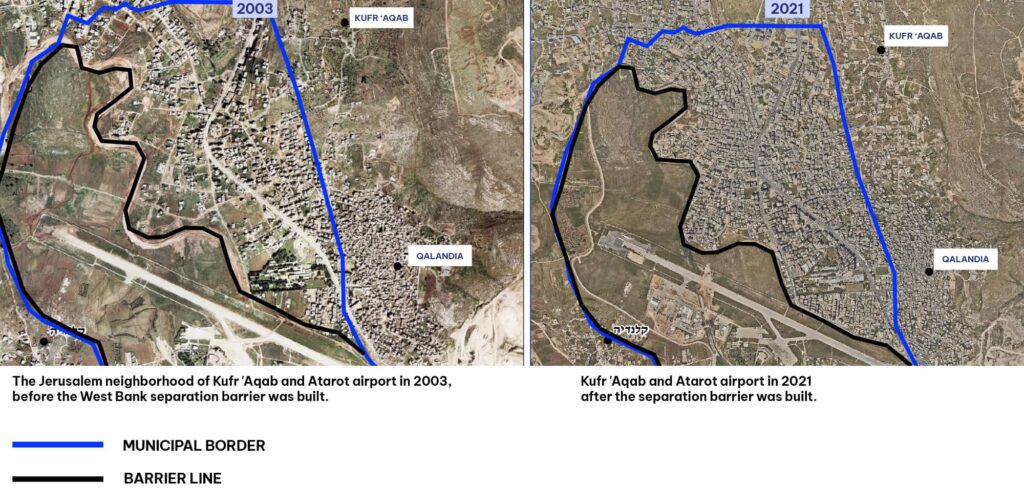

Back to my friend in Kafr ‘Aqab: The separation barrier does not fully correspond with the municipal border drawn in 1967. Most significantly, the village of Kafr ‘Aqab and the Shu’afat refugee camp are inside municipal Jerusalem but outside the separation barrier. The fear of losing Jerusalem residency drove an estimated 80,000 people in these neighborhoods to move inside the separation barrier – driving real estate prices sky high. At the same time, a counter real estate trend emerged: the two neighborhoods outside the fence but inside the municipal borders became a cheaper housing alternative, and one which retained easy access to the West Bank.

Thus, among the 370,000 Arabs in East Jerusalem, spread over 43 square kilometers, no less than 120,000 – nearly a third – crowd into these two neighborhoods of the city which are outside the separation barrier, covering less than 3 square kilometers. The burst of building there began with the barrier, the wish to remain within Jerusalem’s (and Israel’s) jurisdiction and the realities of the local real estate market.

The barrier removed the key reason for neglect. It made for certainty. The barrier is perceived by both sides as the future border with a Palestinian state to come. Israel has for the first time physically signaled to Arabs of East Jerusalem – and to itself – that the Arabs neighborhoods of the city are, and will remain, part of Israel.

The Impact of Certainty

Certainty changed perceptions and conduct on both sides. The Government of Israel (which has a Ministry for Jerusalem Affairs) is increasingly involved in municipal projects in East Jerusalem including public transport and infrastructure – at the total cost, over two five-year plans (2018-2023, 2023-2028) of 1.45 billion US dollars.

City Hall began to draw up master plans for neighborhoods which for many years had been left unattended, and where most of the construction lacks permits. The city, in close cooperation with the Ministry of Justice, is making significant efforts to regularize the unpermitted housing construction retroactively and thus making possible further development, often in dialogue with residents.

On the Arab side, there is a partial, hesitant opening of doors to Israel – specifically regarding employment and education. Hebrew courses have turned from a taboo sign of tatbi’ or normalization with the enemy, to a sought-after privilege; dozens of Hebrew language study locations have popped up. The Israeli high school matriculation program is steadily gaining ground at the expense of the Palestinian one ( a steady rise of 30 percent in recent years).

Requests for citizenship are inching up, and my Kufr ‘Aqab friend believes that an absolute majority of these requests (including his and his wife’s) come from the two Jerusalem neighborhoods beyond the fence, where the residents fear they would lose their link to Israel if a diplomatic compromise leaves them on the Palestinian side of the border.

Thus patterns of migration and registration reflect a preference to remain linked to Israel. This should not be misread, however, as signs that peace is about to break out. Changing attitudes will take years and maybe decades.

For this hope to be achieved in the long run, the road runs through the East Jerusalem education system, where the Palestinian educational system’s matriculation tests are still extant (based on the even more anti-Israel version used in Jordan until 1967). The anti-Israel texts taught in UNRWA schools were highlighted in the media after the radical attitudes and activities of UNRWA workers came to the fore during the war in Gaza. Having seen the UNRWA school texts, I share the concerns. On the other hand, elsewhere in the Arab world there have been successful efforts, especially in the UAE, to weed out incitement and Jew-hatred in the school curricula, proof that it can be done. But it has yet to happen in the Palestinian curricula used in East Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, other factors push in the opposite direction, with fears about Al-Aqsa feeding the rise of Islamist movements who reject all negotiated outcomes. According to the Palestinian pollster Khalil Shikaki, in 2017 only 33 percent of East Jerusalemites thought that the Palestinian goal should be a state “from the river to the sea.” Now during the Gaza war 59 percent do.

This would not be the first case in which social and economic integration generates as a first reaction both radicalization and national-religious self-definition so as to ward off assimilation. Still, extremists who seek to fire up the streets do not necessarily reflect the real-life wishes of the population.

Conclusion

Annexed in 1967, East Jerusalem after 55 years has finally begun to find its way to integration. East Jerusalemites find themselves at the volatile stage of drawing close to a new dispensation on one hand and giving vent to politically radicalized views on the other. The sense of certainty first created by the separation barrier can lead to integration in the city. This does not generate love nor peace, but it does lead to acts of practical reconciliation.

For Israel, certainty should be bolstered by budgetary investments, construction, growing involvement and encouragement to enter local politics. These can slowly steer Jerusalem in the right direction, while neutralizing divisive issues. Working to advance areas of agreement, and avoiding a patronizing approach while dealing firmly with any threats to security and attempts to violently disrupt the integration – this can lead the city to a better future in the long run.

Internationally, those who seek peace would do well to invest in drawing the two sides living in the city together, not apart: reducing the intensity of conflict, monitoring incitement on both sides, and investing in education for tolerance. Good neighborly relations are possible in this city and there are signs that, even in an environment of war in the region, they are growing.