Congress has never had an easy time passing defense budgets. Despite partisan bickering, however, the Congress has successfully passed 62 consecutive defense authorization acts, including for the current year.

The upcoming year’s budget appears to be a troubling exception. Sadly, the best-case scenario is for a defense budget that will be reduced for a time by one per cent, if Congress is unable to pass all twelve appropriations bills by January 1. This political stalemate comes against the background of a shrinking military in the face of ongoing threats.

>> Window on Washington: Read more from Dov S. Zakheim

Increased costs and program delays have resulted in a shrinkage of American military force levels. The Navy’s decline has been the most dramatic. The fleet currently stands at just under 300 ships, a far cry from Ronald Reagan’s “600 ship Navy,” and well short of the service’s latest goal of 381 ships, a number that does not include its plan for some 150 additional unmanned units. The current Senate and House bills for next year prevent the administration from retiring ships that have not reached the end of their service lives (four to five ships). Both House and Senate bills also authorize a new ship, the Amphibious Dock Landing Ship. Nevertheless, the Navy will still fall far short of its goals.

Background of Multiple Threats to America

While Washington fights over aspects of the defense budget, as described below, China is continuing a multi-decade military buildup. Its latest budget calls for an increase of 7.2 per cent in defense spending. That budget notably does not include spending on space and other research programs, while its personnel costs are minimal compared to the pay and benefits that the American defense budget provides for the American all-volunteer military (this year’s defense authorization bills call for a 5.2 per cent pay increase, the highest in two decades). Despite China’s current economic difficulties, there is no indication that the military budget will be affected.

China is not of course the only threat facing America. Its forces, together with those of its NATO allies, must deter Russia in Europe while continuing to support Ukraine’s effort to recover lost territory. America continues to retain a considerable presence in the Middle East to deter Iran. It must also support South Korean efforts to deter a bellicose North Korea that continues to press on with its nuclear weapons and long range missile programs. Finally, the United States still deploys forces to fight a reduced but still potent international terrorist threat.

The Administration Request and Congressional Response

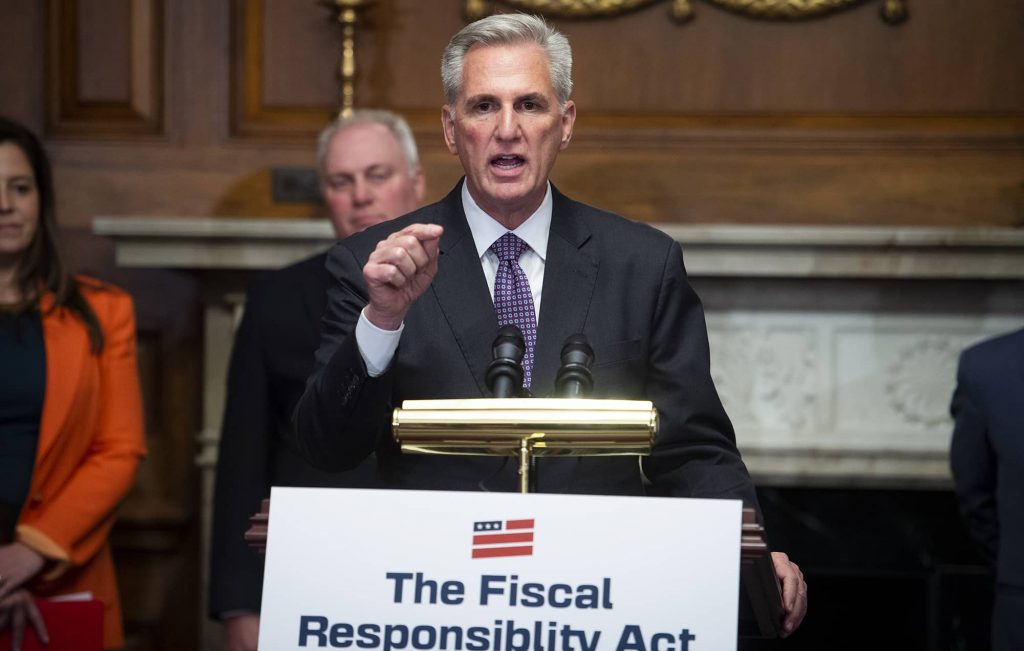

The Biden administration request has $28 billion more for defense for the upcoming fiscal year than it received in last year’s budget, a 3.2 per cent increase. [The US Government’s fiscal year runs from October through September, thus fiscal year 2024 starts on October 1, 2023.] Both the House Armed Services Committee and the Senate Armed Services committee have completed their bills, approving budgets of $844 billion that roughly approximates the Biden administration’s $842 billion request. Both administration and Congress are abiding by the terms of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (which raised the federal debt ceiling in exchange for budget limits).

But the administration’s budget assumes annual inflation of 2.4 per cent (considerably lower than the actual rate). Thus while the defense budget coming out of the congressional committees is virtually flat in nominal terms when compared with the previous year, it represents anywhere from a one to a five per cent decline in real terms after accounting for actual inflation.

The two congressional committees support many of the administration’s requests, especially with respect to cutting edge technology such as artificial intelligence and various space programs. They also pour additional funds into numerous other programs. These include a nuclear-armed sea-launch cruise missile despite the administration’s strong opposition and a new warhead for the cruise missile. The committees also increase funding for the Sentinel land-based strategic ballistic missile and for defenses against hypersonic systems. They also prohibit the administration from reducing the current inter continental ballistic missiles (ICBM) force below four hundred missiles.

The House committee adds a glide phase missile defense interceptor (while the Senate committee requested a briefing on the program) and accelerated the development of an East Coast missile defense site. It also adds $50 million to the president’s budget for high-tech research and development cooperation with Israel. The Senate committee adds funds for, among others, the Army’s Pathfinder-Airborne program which promotes innovation by members of the lower ranks, enhanced night vision goggles and other high tech innovations, cyber defense activities and analysis of cyber threats to the semiconductor industry.

Politics of the Defense Bills

Despite strong support for the authorization bills in the two armed services committees, passage into law remains in doubt. The House bill included some “anti-woke” measures championed by the Republican caucus. These include banning any funding for DoD programs related to “critical race theory,” ending DoD diversity, equity and inclusion programs, eliminating funding for drag shows, allowing parents to review books included in the curricula of the DoD’s school system, and refusing to authorize climate change-related programs. While the Senate committee accommodated some concerns, such as requiring a briefing on parental involvement in school curricula, it did not include most of the others.

Most observers anticipate that the House committee will drop some of these provisions when the two committees meet in conference. Nevertheless, even if that proves to be the case, the conference bill still requires approval on the part of both Houses of Congress. Right-wing members of the House are threatening to block the bill’s passage unless it includes every one of their demands. Without their votes, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy would have to rely on the Democrats to pass the bill, something he is loath to do, since it could lead to his removal from the Speakership.

While passage of the authorization bill remains in doubt, even bleaker is the outlook for the defense appropriations bill. To begin with, the probability of agreement between the Senate and House appropriations committees is virtually non-existent. The House defense appropriation reflects what the Republican majority committee terms “conservative priorities.” These include bans on the following: “the implementation, administration or enforcement of…executive orders on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion,” “the use of funds [for] medical procedures…to change an individual’s biological gender,” funding “to promote or advance Critical Race Theory,” and “the use of funds for paid leave and travel or related expenses…for the purpose of obtaining an abortion or abortion-related services.” The Democratic majority in the Senate will not give in to these provisions. Stalemate is in order.

Moreover, according to the budget limits of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, all twelve appropriations bills for the entire federal government must pass before January 1, or the president’s budget request would be cut by one per cent below last year’s levels until all the appropriations win congressional approval. As of mid-August, only one of the 12 – the military construction and veterans’ affairs appropriation – had passed the House, and even that normally uncontroversial bill barely won committee approval. A number of congressmen are lobbying for even deeper cuts than one percent of the fiscal year 2023 defense budget. They wish to revert to the fiscal year 2022 levels of two years ago.

If these disputes were not enough, there is growing opposition to further assistance to Ukraine among House Republicans, who want to see European countries shoulder a greater portion of the Ukraine burden. On August 10, the Biden administration put forward a request for yet another Ukraine supplemental that totaled $24 billion, of which $13 billion was to replenish dwindling US ammunition stocks as a result of previous transfers to Ukraine. This supplemental is unlikely to cover more than the next three months of support to that embattled country. Another supplemental will likely be needed but will face even greater opposition from House Republicans, including Speaker McCarthy, who has already announced his opposition to the supplemental currently before Congress.

With only a few working days left until the current fiscal year ends on September 30, Congress is unlikely to pass anything other than a continuing resolution to keep the government funded at current levels. That would prevent virtually all new program starts. But another possibility is a government shut-down starting on October 1, with no indication as to how long it might last.

America’s allies and friends have been watching these developments in Washington with justifiable anxiety. Her adversaries could not be more pleased.