Not since the Oslo Accords of 1993–1995 has an aspect of Israel’s relations with an Arab neighbor aroused such vehement argument in the Israeli public. Unlike the Oslo Accords, however, this is not a bilateral agreement signed in each other’s presence as Lebanon refuses to deal with Israel directly, in any manner that would imply some form of recognition. Thus, as the clock ticked away before Israel’s November 1 parliamentary elections, and the expiration of Michel Aoun’s term as president of Lebanon on October 31, a US-sponsored understanding was reached with each of the two countries signing a letter to the US government (which would also be deposited with the UN) that delineates an agreed-upon maritime boundary between each country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), as well as parts of their territorial waters.

Israel’s opposition, led by former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, repeatedly accused the “weak and inexperienced” Lapid government of surrender (or even betrayal), throwing away Israel’s potential assets. The government, backed by the views of the defense establishment, claimed that the arrangement would benefit Israel’s economy, remove the threat of war, and may constitute a historic turning point in the long, sad history of relations with Lebanon. It portrayed Netanyahu’s position as irresponsible warmongering.

Lebanon’s reluctance, mentioned above, to directly deal with Israel did not help the proponents of the arrangement in making their case. Moreover, Prime Minister Lapid spoke of averting a clash, which made it look as if he had surrendered to the threat of violence. Five points of bitter contention stand out:

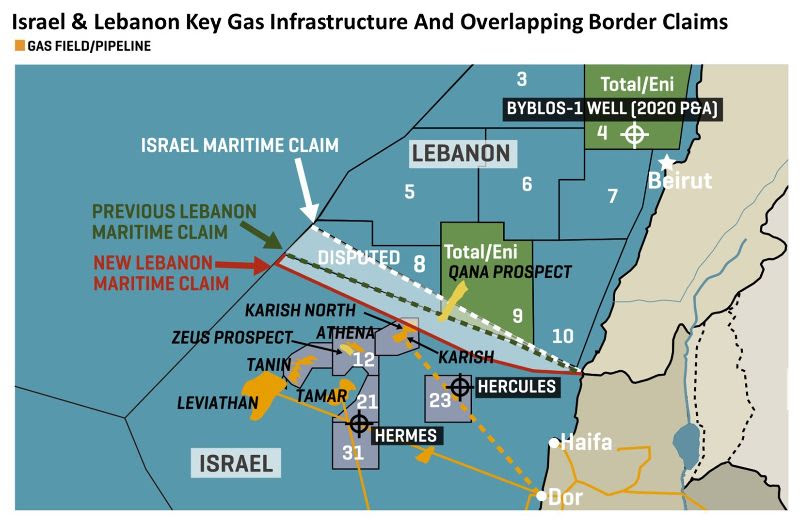

- For well over ten years, various suggestions have been made as to an equitable middle line at sea between Israel’s more northerly claim and Lebanon’s, with a triangular area of 860 square kilometers in area between them (see map). Israel had been willing to settle for half or less. Still, in recent months, the Lebanese government raised an outlandish claim to an even more southerly line. In response to this tactic, Israel decided to agree to Lebanon’s original line, if Lebanon would accept—as a fact of life, not in legal terms—the current situation (the “buoy line”) of the territorial waters next to the shore. For the Israeli proponents of this arrangement, it was a reasonable concession, aimed at giving Lebanon a significant stake in gas production and hence in stability. For its detractors, it was a shameful and harmful failure to defend Israel’s rights.

- Perhaps more important than the actual line was how Hezbollah inserted itself into the fray. It launched a few unarmed drones toward the production platform in the Karish field, which lies in Israel’s EEZ, but also partly within Lebanon’s second, more southern line made late in the negotiations by Lebanon. Hasan Nasrallah was signaling that conflict may erupt over the gas. This led many in Israel to accuse their government of a retreat under the threat of violence, causing grievous harm to the all-important concept of deterrence. As key Israeli players kept saying, Israel wants Lebanon to gain and to have a win-win stake in stability. Hezbollah thus faced a real threat to the very legitimacy of its position in Lebanon. If Israel is not really an enemy and even shows generosity to help Lebanon survive economically, what excuse is there for Hezbollah to remain independently armed against “the Zionist entity?” The organization and its Iranian masters thus had to play up their threat, to make Israeli magnanimity look like a surrender to blackmail. Careless Israeli language added to that impression.

- The direct economic gain to Israel from the future exploration of the Qana field, which lies largely within the Lebanese EEZ as now agreed, is bound to be marginal. The real benefit would be that Lebanon would have a stake in stability of the maritime border and that gas production in Israel’s Karish field could begin (as indeed it has on October 26). Folly, retort the detractors: it will be years before any income materializes, and Hezbollah’s grip on Lebanon is so firm that the national economic interests would be easily cast aside once the organization finds a reason for conflict with Israel. What you fail to see, answer the proponents, is that gas production in the Eastern Mediterranean has been made so much more lucrative by the war in Ukraine. It has also become ever more important as a key component of the strategic relationship with Egypt. These are two reasons why a future Israeli government, even under Netanyahu, may ultimately be wary of reversing the present government’s decision (Netanyahu is on record saying he would treat this like the Oslo Accords, which he reviled but did not reverse).

- The detractors raise a valid constitutional point: A major concession affecting Israel’s national rights cannot be implemented without a referendum—under a law from the 1990s—or at least a Knesset vote. The prime minister did secure an opinion from Attorney-General Gali Baharav-Miara that the arrangement regarding the maritime boundary can be implemented by government fiat, an opinion which the Supreme Court upheld. Still, politically, it’s difficult to avoid the impression that Lapid and his colleagues were in a hurry to translate this into electoral gains (a steady plurality of Israelis support the arrangement, if the polls are to be trusted). But it is also difficult to ignore the brutal political edge of the criticism—much of it ad hominem—hurled by Netanyahu and his allies.

- Finally, another significant point of contention has surfaced: a sense of distrust among many in the nationalist and religious right toward the military high command and the defense establishment. The latter are suspected of being too soft on Israel’s enemies and too attentive to American pressures. These are the people, tweeted one Likud member of Knesset, who gave us the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the 1982 mess in Lebanon, and the 2005 withdrawal from Gaza.

The present acrimony may reflect a broader agenda that might have an impact on the elections and their aftermath.